Population ageing has many consequences for a country's wellbeing, including impacts on economic growth, employment rates, health conditions, and the availability of resources. This is a critical issue in a country like China: according to the World Health Organization, this country "has one of the fastest growing ageing populations in the world", with 402 million—or 28% of the population—expected to be over 60 by 2040.

Yaohui Zhao, a professor of economics at Wuhan University in China, believes that understanding labour market dynamics and factors that influence healthy ageing can help fostering more equitable societies. Her pioneering studies on the Chinese labour market won her the 2024 TWAS Siwei Cheng Award in Economic Sciences.

"As an economist, I realized that one major goal would be to understand the roots of poverty and advise policymakers on the importance of safeguarding the most vulnerable people in the low- and middle-income social classes," she said.

"The TWAS Siwei Cheng Award is not only a personal honour, but also a tribute to an often-forgotten cause: the female condition," she added, stressing that women are disproportionally affected by ageing. This is because they live longer in the widowhood state, with worse health conditions, and have fewer economic resources, she noted. "They pay the highest price because of their gender, and I am deeply committed to bringing new awareness in this field."

When do we become old?

Old age is not always defined by the date on the birth certificate. At a biological level, ageing is associated with an increased number of molecular and cellular damages. However, being self-sufficient in daily life, having cognitive flexibility and an active life and, in general, good health may often disprove the chronological age.

According to a study that Zhao has co-authored, China is home to a fifth of the world’s older people. In 2020, Chinese people aged 65 or more there were about 172 million, and projections suggest that they will peak to 366 million by 2050. This poses several challenges due to a combination of factors including the decrease in the number of living children for each older person, and the increased number of retirees relative to people in the workforce.

"An urban worker retires at age 60 or earlier. Unfortunately, farmers do not have generous worker retirement benefits," Zhao explained. "Also, age is not the only factor, other ageing indicators are relevant for predicting good or bad ageing path. They are the ability to take care of themselves, to live on one's own without being assisted, to dress autonomously, and to go in and out of bed without assistance."

When they retire, well-to-do people stop working and start looking after their grandchildren. However, individuals from low-income groups, especially in rural areas, keep working until they become disabled or rely on their children for economic support. In addition, the lack of financial resources may exacerbate conditions such as depression, pain, and cognitive decline. Furthermore, bad habits like smoking, and environmental pollution worsen the situation.

To facilitate the understanding of how ageing affects people and how to age in good health, in 2007 Zhao initiated and led a national cohort study called the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). So far, the study has collected data seven times over the years to monitor changes. More than 120,000 scholars accessed the data, resulting in the publication of over 6,000 papers.

Zhao also chaired the commission that wrote the article The Path to Healthy Ageing in China: A Peking University–Lancet Commission, published in the medical journal The Lancet, in 2022, which is now a benchmark study for ageing policies in China.

One of the article's core messages is that older people are a resource for the society because they can still be a productive force rather than a burden.

Family matters

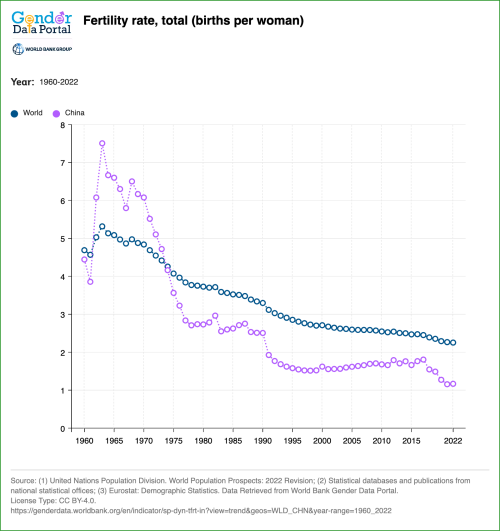

"When we analysed the women's point of view, we found that bringing a child into the world is perceived as an event with high costs and negative impacts on the employment," the economist said. She also noted that although families are still important in China, people have fewer children than in the past.

Furthermore, the household income has an impact on how parents raise their children. "Poor families, in particular, rely on grandparents for childcare support, and leave their children with the grandparents when they move to urban centres seeking better jobs."

These so-called "left-behind children" are a far-reaching phenomenon in China, where 61 million rural kids are living apart from their parents after they migrate to urban areas. Growing up with "surrogate caregivers" may compromise their cognitive and physical development, as well as their overall well-being.

"Children are tomorrow's adults, and separation from their parents increases the risk of future psychological disorders like anxiety, psychosis and stress," Zhao said. "With my working group, we have advised the Government to help families by lowering the cost of childcare and providing accessible, low-cost services to the poorest families."

Women and ageing

During her career, Zhao has never ceased encouraging women to step up for their career. From 2002 to 2102, she has co-directed the Chinese Women Economist Research Training Program at Peking University in Beijing, providing research training and mentoring to more than 200 female college professors and researchers nationwide.

"Many female professors were unable to improve their professional status because they didn't know how to produce high-quality, competitive research," Zhao explained. With her group, she organized intensive training courses and lectured on topics ranging from gender discrimination to using statistical software. After this training, many women economists progressed from junior to senior positions, with some eventually becoming department chairs, school deans, or university presidents.

"Through this programme, we succeeded in elevating the status of women in the economics profession," she recalled. "But there is still a long way to go." Upon moving to Wuhan University as a senior professor in humanities and social sciences in December 2023, she realized she was the only woman among the seven professors in the highest positions.

Yet, she always encourages women to be more assertive and proactive in competing for resources. "That's because they are disadvantaged with respect to their male counterparts, less remunerated, less represented, and unable to make their voice heard," she observed.

This is why she plans to continue the CHARLS project for another decade. "I want to improve this survey and make it a more productive tool to enhance our understanding of health and ageing issues in China, especially for women."

Cristina Serra