Despite progress in research and therapy, infections caused by HIV are still a global public health issue. At the end of 2021, an estimated 38.4 million people were living with HIV; roughly two thirds of them are in the WHO African Region. And about 1.4 million of them live in Uganda.

Damalie Nakanjako is a Ugandan physician with 22 years of experience in infectious diseases care and Principal of the College of Health Sciences, at Makerere University, in Kampala, Uganda. She devoted her career to fighting HIV and other major diseases, such as tuberculosis. Her research is now paving the way for reducing the HIV burden in Uganda.

In 2022, she received the TWAS-Abdool Karim Award, which honours women scientists in low-income African countries for their achievements in biological sciences. Nakanjako conducts clinical research on the mechanisms of immune activation, inflammation, and recovery of immunity during chronic HIV infection. This work is improving how much access people have to HIV diagnoses, and help managing Tuberculosis-HIV co-infections.

"This award is a springboard to help me focus on prevention and management of complications of chronic HIV treatment and for finding a cure for HIV," she commented.

Living with HIV

The acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is a chronic condition caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which damages the immune system and reduces the body's ability to fight infections. Deciding to help people infected with HIV was a natural choice for Nakanjako. In 1982, Uganda was the first African nation to identify AIDS cases within its borders, and it would become one of the worst-hit countries on the African continent.

In recent decades, however, the AIDS burden on Africa has changed. Once, people with HIV had no access to treatments. Now, they receive life-saving antiretroviral therapy, a combination of different medicines that people with HIV take every day to reduce the viral effects.

"Living with HIV makes people more exposed to other infections and to admission to hospitals," Nakanjako said. Diarrhoea, for example, is a common condition in rural communities that do not drink treated, safe water. But few interventions are still available for people in Africa.

In a study published in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, Nakanjako tested the effectiveness of simple measures to reduce diarrhoeal diseases among people living with HIV. By providing a group of HIV-positive people with tools to disinfect water and offering hygiene education, Nakanjako and her team got valuable results. "The safe water supply in combination with daily antibiotics reduced the diarrheal episodes by 25%, and decreased hospital admissions," she said.

She and her colleagues followed up by distributing insecticide-treated mosquito nets as a basic package for all people living with HIV. Their aim was to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with opportunistic infections—infections that occur more often, or in a more severe form in people with a weakened immune system. One example is malaria, which is transmitted through the bite of infected Anopheles mosquitoes and often affects people with HIV.

HIV-related diseases

Even if the current available therapies keep HIV from being a death sentence, those who live with this virus experience other health issues, such as the early occurrence of age-related diseases.

"Chronic inflammation caused by AIDS is associated with earlier episodes of aging diseases among people who test positive for HIV," Nakanjako explained. "In our community in Rakai, Uganda, we found that blinding cataracts occurred two decades earlier among people infected with HIV, with respect to uninfected people in the same community." Her study on this topic was published in the scientific journal Immunology Letters.

Tuberculosis is another HIV-associated disease. As reported by UNAIDS, people living with HIV are 18 times more likely to develop Tuberculosis, which kills more HIV-positive people than any other disease.

Nakanjako's work has contributed to the development of algorithms for Tuberculosis screening, diagnosis and treatment in health care facilities that manage all stages of HIV diseases, as she reported in an International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease study.

High-impact health care programmes

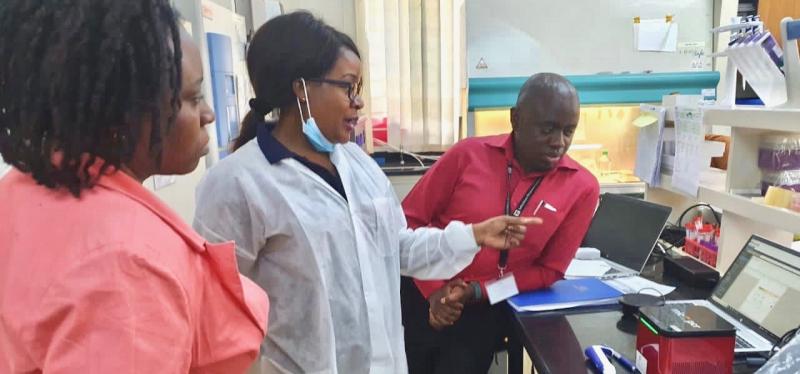

Nakanjako’s scientific research is not the whole story. She is also committed to strengthening her community’s ability to manage its healthcare needs.

To ease restrictions imposed by Uganda’s healthcare workforce scarcity, Nakanjako has participated in a health leadership training programme. The goal was to equip health care providers in resource-scarce settings with the skills needed to lead high-impact health care programmes.

For four years, she has also chaired the research and ethics committee of the Uganda Cancer Institute, and she currently is on the board of directors of several other major Uganda healthcare institutions.

She is also coordinating local outreach activities, both in research and care programmes. ‘Friends of IDI’ is a group of HIV-positive people who participate in a programme offering activities such as community plays at Makerere University’s Infectious Diseases Institute. Patients, she explained, have also learned to make beautiful crafts that they sell at the clinic and in their communities, as part of their entrepreneurship training.

The TWAS-Abdool Karim Award that Nakanjako received has further motivated her in continuing her research and outreach activities.

"I was very excited to learn that I have been selected,” she said recalling the moment when she received the news of the award. “I immediately shared the news with my mentors, and family, who have supported me in my daily endeavours and cheered me to continue doing what excites me."

Her future plans are to create a strong network of skilled scientists and health care professionals to develop solutions to global health challenges. Because, she stressed: "We are not safe until everybody is safe.”

Cristina Serra