Agriculture is a vital sector for Nepal, involving about 66% of its population. But the still-prevailing subsistence farming model and the country's vulnerability to natural disasters result in low productivity, as well as hardships for farmers.

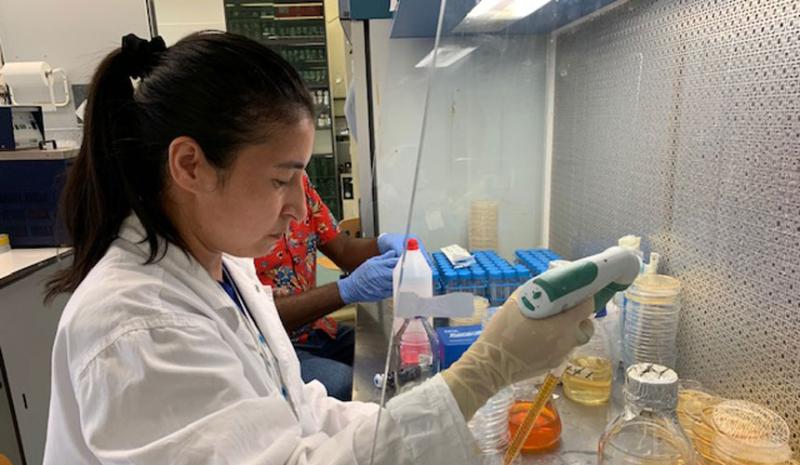

Biochemist Pragati Pradhan, from the Central Department of Biotechnology of Tribhuvan University, in Kirtipur, Nepal, aims to improve agricultural practices by introducing DNA analysis techniques in bacteriology.

Pradhan is a participant in the TWAS-SISSA-Lincei Research Cooperation Visits Programme. For three months—from 6 May to 3 August 2022— she worked in Vittorio Venturi's bacteriology lab, at the International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (ICGEB), in Trieste, Italy. There, she identified bacteria that are potentially useful for coffee plants.

"The TWAS-SISSA-Lincei Programme was a new beginning for me. I explored new laboratory techniques and became familiar with microbiology and molecular tools in the bacteriology sector," she said. "Despite the short training period, I gained basic knowledge and understood the importance of plant growth-promoting bacteria called rhizospheric bacteria, or rhizobacteria. These techniques will definitely help me to improve my career prospects and become a good researcher."

The TWAS-SISSA-Lincei programme promotes collaborative links between least developed counties (LDCs) and Italy. Under this programme, young scientists from LDCs can visit research laboratories at centres of excellence in Trieste, Italy, for three months. This allows them to carry out collaborative research projects in fields that fall under the umbrella of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

After they return home, the scientists continue the collaboration initiated by the visit. The Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation and the Italian Agency for Development Cooperation financially support the programme.

Pradhan's project is related to SDG 2, Zero Hunger, and SDG 15, Life on Land. Through the techniques that she is introducing in Nepal, farmers may expect to obtain higher crop yields. The same techniques, if correctly applied, may lead to more sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, avoiding the use of pesticides and chemical fertilizers.

Pradhan's first visit ever to Italy was challenging. She knew just a few words in Italian and also the scientific field was a brand new one to her. But she accepted the challenge and made the most out of the experience. "To overcome some hardships, I developed the habit of interacting with people, asking for clarifications when it was the case," she explained.

Now that she is back in Nepal, she is applying her new knowledge to the benefit of students and colleagues in her department.

How do bacteria help plants grow?

Plant roots are home to scores of microorganisms, many of which provide benefits to the vegetation. Some bacteria found in roots, in fact, turn nitrogen into ammonia, making it available to the plant and enhancing its growth.

Other bacteria add nutrients to the soil and produce antibiotics, hormones and other substances that are useful for the plant. In exchange, plants provide microorganisms with carbon and the aminoacids that they need to thrive. Altogether, bacteria and the surrounding plant roots with their secretion form the rhizosphere, a lively yet poorly investigated environment.

Detecting good microbes and understanding their potential as growth-promoting agents is central to breeding stronger varieties of plant foods. At ICGEB, Venturi has been studying the rhizosphere for more than two decades.

"Identifying bacteria living in the coffee rhizosphere is critical if we wish to understand their potential as plant boosters, especially in view of the importance that coffee has for many developing countries," Pradhan said.

Now, these bacteria are available to Venturi's team, which is further analysing their potential. But Pradhan will continue working on microbial ecology, an increasingly popular field that she is now exploring. Her aim is to come up with innovative research projects at Tribhuvan University, leading to potential new applications in agriculture.

Coffee is not one of the most important commodities in Nepal, but crops like maize, millet, rice and wheat are. And due to land degradation and lack of agricultural innovation, yields for these major crops are too small for the ever-growing local population.

"Working with bacteria that can promote better growth of Nepalese crops means boosting a stagnant agriculture and exerting long-term effects on the national economy," Pradhan said. "I can apply some of the results obtained in Italy to Nepalese rice plants. I will use specific bacteria instead of chemical biofertilizers or pesticides, to obtain thriving varieties."

In addition to her lab work, Pradhan also engaged in lab presentations. In Trieste, she presented the research projects she carried out in Nepal and the results she obtained over three months at ICGEB. "The most important thing that I learned from this experience is to believe in myself and keep being motivated to learn more about this research topic and lab techniques. What I learned during my visit made me more confident and more determined," she added.

What does Pradhan expect for her future? "I definitely wish to keep in touch with Prof. Venturi, my mentors and lab mates at ICGEB. And I plan to use my experience as an example, to motivate students exchange programmes with Italy, and build a community of skilled scientists who can help Nepal thrive."

Cristina Serra