Elizabeth Njenga recalls the science diplomacy courses she attended as not only informative, but a creative experience. A botanist from Kenya, she said that the courses’ simulations illustrated how science and international relations intertwine, and why thoughtful scientific advice is indispensable for good diplomacy.

“I would say that the second training, which was hands-on, enchanced my skills, thus enabling me to conduct and facilitate trainings in science diplomacy,” she said. “This training in Trieste was not just academic, but rather an application of science diplomacy for addressing global challenges.”

Njenga is just one of 344 alumni of the AAAS-TWAS Science Diplomacy Course. Since 2014, AAAS and TWAS have held nine courses, most of them held in-person in Trieste, Italy, and the programme has become a major fulcrum for science diplomacy education, especially for scientists from developing countries. Course alumni are now influencing policy and spreading knowledge about the fast-growing science diplomacy field throughout the developing world.

The course is the result of a collaboration between the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) and TWAS, with key funding from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida).

Njenga is a graduate of two AAAS-TWAS Science Diplomacy Courses, one in 2018 and the other in 2019. When she began the training, she was a botany professor and researcher with the University of Eldoret in Kenya, a position she still holds today. She is also formerly a vice chair of Kenya’s chapter of the Organisation for Women in Science for the Developing World (OWSD). The 2019 course in particular was designed as a unique “train the trainers” course, inviting previous graduates back a second time to provide them with additional skills needed to spread their own knowledge on science diplomacy to others.

After the 2019 course, Njenga discovered that many of her colleagues at other African universities were indeed interested in an Africa-centred course. But she had trouble organising such a meeting because of the COVID-19 pandemic and its ensuing lockdowns.

But she was nonetheless able to put her new skills in science diplomacy to good use. In 2020 she established an international relationship for sharing data on COVID-19 with another 2019 course alumna, Monika Jaggi of CSIR-National Institute of Science Communication and Information Resources in India. This South-South collaboration still continues today, Njenga said.

Later, she was able to coordinate a breakout session on science diplomacy for an international Women in Science Without Borders conference at the University of Embu in Kenya. After that, she wanted to organise a small, Africa-centred workshop specifically to give African professionals the opportunity to learn what science diplomacy is.

The resulting science diplomacy training event, in April 2022, had 54 attendees from eight African countries, including experts from both academia and government.

“I take this opportunity to thank TWAS, AAAS, Sida, and the rest of the team for giving me the opportunity to train in science diplomacy, two years in a row,” Njenga said. “That was such a great honour, and I didn’t take it for granted. I have tried my best to make use of what I learned from the training to sensitise people on aspects of science diplomacy.”

What is science diplomacy?

Science diplomacy is a broad way of describing how scientific teamwork between nations can solve shared challenges and improve international relationships.

Nations and cultures have long built relationships based on science. But the modern era of science diplomacy emerged in the latter half of the 21st century, when the United States used scientific research and exchange as a basis for building better relationships with China and the Soviet Union.

Today, science diplomacy takes many forms. Science can support diplomatic efforts, such as when researchers provide insight to support a new treaty to protect oceans. Diplomacy may also help lay the foundation for a multi-national science project, such as the Synchrotron-light for Experimental Science and Applications in the Middle East (SESAME) in Jordan. Scientific cooperation can also begin with the explicit intention of improving relations. Increasingly, nations are placing scientific attachés in their overseas embassies.

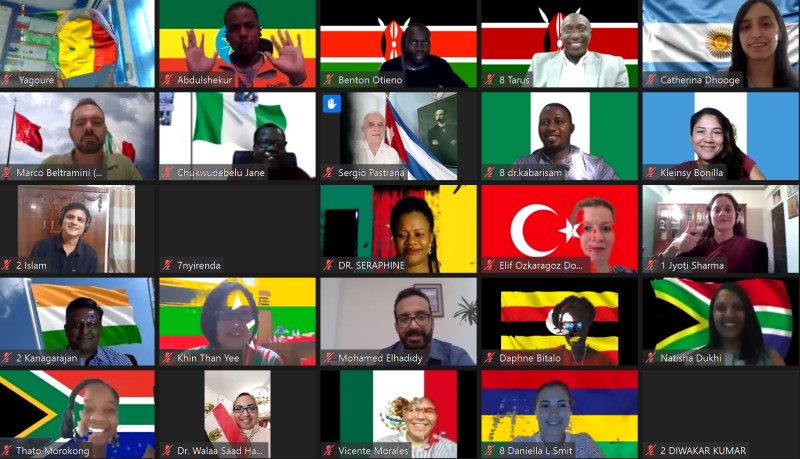

As a global science academy dedicated to building scientific capacity and expertise in developing countries through international collaboration, science diplomacy has been a natural area of focus for TWAS. The Academy signed its agreement with AAAS to host science diplomacy workshops and courses on key international challenges in 2011. TWAS has since hosted a science diplomacy course every year since 2014. The course moved online for three years, from 2020–2022. The tenth course is scheduled to take place from 19–23 June 2023, and will return to being an in-person event at TWAS’s home city of Trieste, Italy.

The course enables attendees to build a skillset that paves the way for careers at the intersection of science and diplomacy. As part of a strategy to strengthen ties between scientists and policy experts, this year the course invited applications from “participant pairs”—a scientist and a policymaker who live and work in the same country who share a common interest in an area of science, technology and innovation.

Putting international skills into practice

While many course alumni are educating others in science diplomacy, some are also putting their training directly into policy work in their home countries. This includes some of the least developed countries, including Lao PDR.

Sengphachanh Sonethavixay of Lao is an alumna of the 2015 science diplomacy course. At the time, she was a policy research manager for National Agriculture and Forestry Research Institute of Lao PDR (NAFRI). She now provides technical and scientific advice to numerous international organisations, including the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

Sonethavixay said that, since attending the course, she has been more focused on policy research, and how to conduct evidence-based research that supports policymaking. Her areas of focus include water resources, agriculture, climate change, and energy efficiency.

“The course is only a five-day course, but we really boil down science diplomacy,” she said. “It helps us to understand how evidence-based solutions can feed into diplomacy. And I’m involved in different projects in which I can apply this knowledge.”

As a consultant for FAO, she develops frameworks for green and sustainable agriculture for Lao PDR, and translates the national policy into agriculture practices on the ground. Her work also entails defining key terms and balancing how the push for organic products influences the reality for Laotian farmers. One policy brief for the FAO that she contributed to found a need for evidence-based research on how to improve benefits from exports for Laotian smallholder farmers.

“Some farms have only one elderly farmer, or perhaps they only have a husband and a wife,” she said, describing the challenges smallholder farms face. “And organic agriculture cannot use pesticides and herbicides. And if you don’t use fertiliser, your vegetables can be thin and small.”

While her work is primarily at the national level, much of her work has a significant international component, which is where science diplomacy comes in. She recently began working on a dialogue on the potential exports of agricultural products from Lao to China, which is increasingly interested in “green agriculture”. Her work contributes to the Laotian negotiation team’s determinations on what their agricultural system can produce before signing any agreements.

Without evidence-informed production guidelines, she said, an agreement can’t be reached. And often her policy advice needs to account for research from and the interests of both her own and other countries. “Like it or not,” she said, “we have to refer to both research in Lao and the market demands in China.”

Career advancement through global perspective

Thato Morokong from South Africa is an alumna of the first online version of the science diplomacy course in 2020. At the time, she was with the Academy of Science of South Africa (ASSAf). She has since become an Assistant Director for Africa Multilateral Cooperation at South Africa’s Department of Science and Innovation (DSI).

Morokong recalled that she joined the course because she wanted a broader perspective on international relations. She now coordinates international projects addressing topical issues such as renewable energy, sustainable agriculture, food security, and enabling innovation.

“I was reading up a lot about science diplomacy, and at the time, the organisation I was working for coordinated numerous science diplomacy initiatives. After seeing my colleagues attend the training course and upon hearing their feedback and experiences, I was intrigued and decided to apply for the training. And I was selected for the 2020 cohort of trainees,” said Morokong.

She said that her career has seen clear improvements since she took the course three years ago. She’s now conducting more research, pushing for more women in STEM leadership positions in key research institutions, and using lessons from the course in her role at DSI.

“The biggest lesson for me was the lesson of multilateralism,” she added. “If you work with a number of partners, it’s all about mutual benefit and reciprocal agenda setting to achieve an impact on different needs. The agenda must be beneficial for different regions, countries, and contexts.”

She cited the LEAP-RE project, the Long-term Joint Europe-Africa Partnership for Renewable Energy, a Horizon 2020 EU-funded project, as an example of how to leverage scientific excellence to address global challenges through diplomacy. Morokong is involved in LEAP-RE through the DSI, which is among the project’s partners.

LEAP-RE is a North-South collaboration that supports cooperation between African and European scientists to develop renewable solutions to energy crises for small-to-medium-size communities. For example, one of their programmes teaches people how to run an independent solar farm. The project convenes over 80 partners between the two continents, including industry, academia, and government.

The reason the lessons on multilateralism helped, she says, is because while renewable energy is becoming a critical issue everywhere, different communities need different solutions. In order to find sustainable ways to meet energy demands for these different regions, science diplomats need to account for how contexts, needs and interests differ between communities.

“The course did give me an upper hand. It paved the way for me to better understand how the policy space works,” she said. “Quite a few of the speakers were policy experts and some were advisors, who talked about how to give policy advice while ensuring that the science is still excellent.”

The course also drove home the importance of science communication for her, because science has to be captured and described in a way that is palatable and well-received by both policymakers and society.

“You find that the science can be prolific, but the manner of delivery isn’t always reachable to the policymaker. Science communication has an immense potential of ensuring the inclusion of everyone in the scientific enterprise,” Morokong said. “They have to work together to reach a common ground.”

Sean Treacy