For scientists who wish to serve the public good in fields such as the environment and health, getting the ear of policymakers is necessary, but often a struggle. Policymakers and scientists, after all, have completely different ways of looking at their jobs. But can researchers use diplomacy to get policymakers to think about science as relevant to their work?

For scientists who wish to serve the public good in fields such as the environment and health, getting the ear of policymakers is necessary, but often a struggle. Policymakers and scientists, after all, have completely different ways of looking at their jobs. But can researchers use diplomacy to get policymakers to think about science as relevant to their work?

The answer is yes, but only if scientists look beyond their comfort zones and accept different tools and expectations that come with policy culture, said three panellists exploring how national circumstances shape science diplomacy.

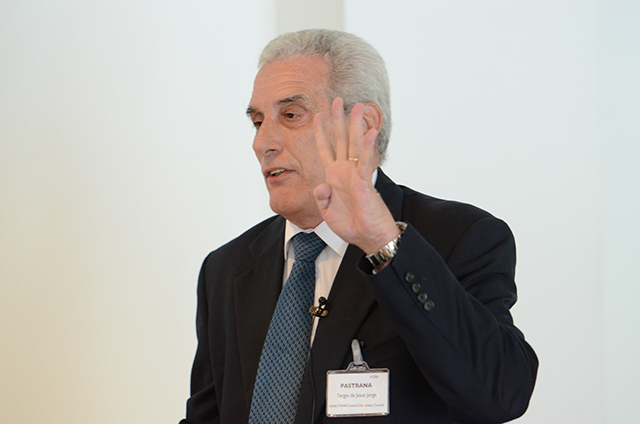

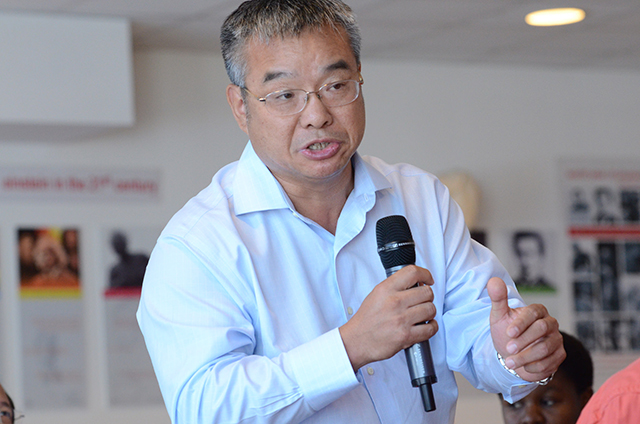

The panel was a focal point of the second annual Course on Science Diplomacy organized by the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) and TWAS at the Academy's headquarters in Trieste, Italy, from 8-12 June. The experts — Cao Jinghua of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), Atsushi Sunami of Japan’s National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies, and Sergio Pastrana, foreign secretary of the Cuban Academy of Sciences — advised an audience of over 50 scientists and policy officials from 34 nations on how their nations have worked to get science and diplomacy to complement one another.

Their advice: You can influence policy through scientific collaboration, an awareness of national circumstances, and a careful understanding of how to communicate. Most of all, constant dialogue between scientists of different countries can help make science an important part of how countries work.

“Do not wait to start. Do not tire easily,” said Pastrana, drawing on his own experience with Cuba’s long-standing scientific relationship with the United States. “And who knows, once you think it’s over, it might be just starting.”

Apply now for the TWAS Science Diplomacy Workshop on Sustainable Water Management! The application deadline is 23 August 2015.

Helping science stand out

Science diplomacy can have a strong appeal to policymakers. For example, public figures often want to stand out, and science diplomacy can help distinguish an official from his or her colleagues. But in order to get policymakers to consider science diplomacy as a part of their agenda, scientists have to learn what policymakers are looking for.

That was a point made by Sunami, the deputy director for science, technology and innovation for his institute. He said that any ideas presented to policymakers on science diplomacy have to be expressed simply and with awareness of the political context.

That way, it’s “not just the scientists talking about the important science, but the foreign international relations people — the foreign policy people — talking about the importance of science,” he said. “So that particular language has to be right.”

That way, it’s “not just the scientists talking about the important science, but the foreign international relations people — the foreign policy people — talking about the importance of science,” he said. “So that particular language has to be right.”

Furthermore, with international work, the language barrier itself can prove a significant obstacle, even with terms such as “science diplomacy” itself. “The Japanese translation for science diplomacy tends to bring out the national-interest-driven aspect much more strongly than what we call diplomacy,” said Sunami. “I think it’s part of the problem we have.”

Sunami said it can be difficult to convince policymakers that scientists should even have a voice within their ministries. One thing that helps in Japan, he noted, was to tie it to an issue they already care about, such as national security.

Policymakers are also always overwhelmingly busy, and researchers shouldn't expect them to be immediately receptive to science-focused policy advice, he said. “So this is one of the difficult tasks, to convince the policy community that science diplomacy is something that’s really good for them.”

Is it diplomacy to simply work together?

But even the word "diplomacy" itself can serve as an obstacle to getting work done. Cao, the deputy director general of CAS’s Bureau of International Cooperation, joined others in saying it’s more useful to speak in terms of international collaborations than of science diplomacy. He said it's often more difficult in his own country and others to innovate in official settings because governments think of diplomacy as a formal, high-level political process that expressly serves national interests.

“Science diplomacy is not new. When I started working in the Chinese Academy of Sciences in 1982, we started to talk about it,” he said. “So, it’s an old concept, and has much overlap with international collaboration. There is a clear distinction, but it’s difficult to define the boundaries.”

“Science diplomacy is not new. When I started working in the Chinese Academy of Sciences in 1982, we started to talk about it,” he said. “So, it’s an old concept, and has much overlap with international collaboration. There is a clear distinction, but it’s difficult to define the boundaries.”

International collaborations that aren't directly administered by government officials give scientists more room to breathe, have more power to build cross-border partnerships over time, and improve the ability of developing countries to conduct scientific work. In that sense, Cao suggested, collaborations have the same effect as diplomacy.

"We can use both terms, yet international cooperation tends to give a broad, unbiased and balanced meaning," he said. "Evidence indicates international scientific cooperation today is playing an increasingly important role in both bilateral and international relations."

Cao said Chinese scientists also face obstacles in diplomatic efforts because of language constraints and because cultivating an international collaboration of substance can take generations. Yet scientific collaborations and exchanges of any kinds have diplomatic value, and countries of many different statuses have a role to play. He called big countries the key, neighbouring countries the priority, and developing countries the foundations. Multi-national organizations, where so many international science projects take place, become the platforms to bring them all together.

“Science is a catalyst for international advances and can help improve relationships between countries in soft, gradual and emphatic way,” he added. “That is why science is so important. Without attaching a lot of clinical implications, it can help mitigate tense situations.”

Scientific talks, warming relations

The perfect case in point may be the long-strained relationship between Cuba and the United States.

Pastrana said science was already a part of negotiations between the two governments, partly as a consequence of previous engagement between his own academy and AAAS, leading to a major agreement between both institutions in April 2014 that laid out plans to advance cooperation between their countries in areas such as emerging infectious diseases. This preceded the historic normalization of diplomatic relations in December 2014.

Though it’s difficult to pinpoint a definite relationship between scientific engagement and a political event such as normalization, scientific links have undeniably been active between the countries despite half a century of estrangement.

“The best partners were not talking because of something that happened 54 years ago. So there’s some absurdity there,” said Pastrana. “But science can deliver, very rapidly, very good results. For instance, during hurricanes, meteorologists on both sides have worked together all along, because the World Meteorological Organization has a system that connects them.”

Pastrana said most of those links are personal relationships between scientists, which in turn become relationships between the scientists' institutions.

“They are colleagues, they are friends, they work together, they call each other,” he added, “and they are in constant communication all along.”

Sean Treacy