New Zealand is a small country with a largely agricultural economy and fewer than 5 million people. It can seem far from the capitals of the developed world, and like many small countries, it is at risk of brain-drain. Despite these challenges, though, the Pacific island nation has emerged as a regional and global leader in areas such as climate change, the battle against obesity, and providing science advice to governments. Last year, it was elected to a two-year term on the United Nations Security Council.

New Zealand is a small country with a largely agricultural economy and fewer than 5 million people. It can seem far from the capitals of the developed world, and like many small countries, it is at risk of brain-drain. Despite these challenges, though, the Pacific island nation has emerged as a regional and global leader in areas such as climate change, the battle against obesity, and providing science advice to governments. Last year, it was elected to a two-year term on the United Nations Security Council.

How does a nation so small and out-of-the-way achieve such strong presence on the world stage? Sir Peter Gluckman, science adviser to New Zealand Prime Minister John Key, says his nation's success reflects a commitment by the government to recognize its strengths in science and use them to advance its interests.

"Small countries need to project their relevance and influence as much as large countries do – and in many ways even more so," Gluckman recently told a TWAS audience. "The large advanced economies have inevitable influence and can protect their interests simply because of their economic and political size. But a small country has to keep reminding the world that we are here, we have something to contribute, we can be a constructive and valuable member of the global community....

"We have to show we are insightful, constructive and nimble. Science is a key part of doing so and indeed, given the inherently global nature of science, science is a particularly powerful way of projecting our voice."

Gluckman's message reflects New Zealand's policy orientation, but small nations North and South can succeed with similar plans. And, he added, science diplomacy can be a critically important area for their strategic engagement.

Science diplomacy "should not be viewed as the domain of the major geo-political powers," Gluckman said. "Small, developed economies need to be – and indeed are – major practitioners of science diplomacy for their own interests and protection. I would go further and suggest that the examples of the small economies have lessons...that may also be of value to developing economies large and small."

A high-impact career

Gluckman delivered the Paolo Budinich Lecture on 11 June in connection with the second annual Course on Science Diplomacy organized by the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) and The World Academy of Sciences (TWAS) at the Academy's headquarters in Trieste, Italy. [See a video of the lecture] Budinich was an Italian physicist who worked with Pakistani physicist Abdus Salam to found the International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) and later TWAS. Gluckman was welcomed by Edi Kraus, the City of Trieste councillor for Economic Development and Tourism.

The course is organized under a 2011 agreement between the AAAS and TWAS to cooperate on science diplomacy initiatives. From 8-12 June, it brought together more than 50 participants and faculty members from 34 nations for discussions, lectures and interactive exercises that focused on how science, diplomacy and communication can be applied to complex regional and global challenges. Participants included current and former high-level officials from UNESCO, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the U.S. Department of State, South Africa's Department of Science and Technology and the Academy of Sciences of Cuba.

Gluckman has had a high-impact career, shifting from his early work as a paediatrician into medical research; in recent years, he has emerged as an influential voice in science policy and the importance of providing scientific advice to governments. In addition to his role as science adviser to the prime minister, he chairs the International Network for Government Science Advice. He heads the secretariat to the Small Advanced Economies Initiative (SAEI) that brings such countries together to discuss areas of science, economic and foreign policy. And he co-chairs the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Group of Science Advisors and Equivalents.

Read the full text delivered by Sir Peter Gluckman for the 2015 Paolo Budinich Science Diplomacy Lecture.

A strategic vision for engagement

Gluckman was appointed science adviser to the prime minister in 2009, and soon was helping to implement a focused strategic effort to foster New Zealand's science-based engagement with other nations. In his TWAS address, he suggested that New Zealand looks carefully for communities and issues where its engagement can be constructive.

For example, New Zealand's southern location gives it a strong interest in the Antarctic, and it works with other nations on research there.

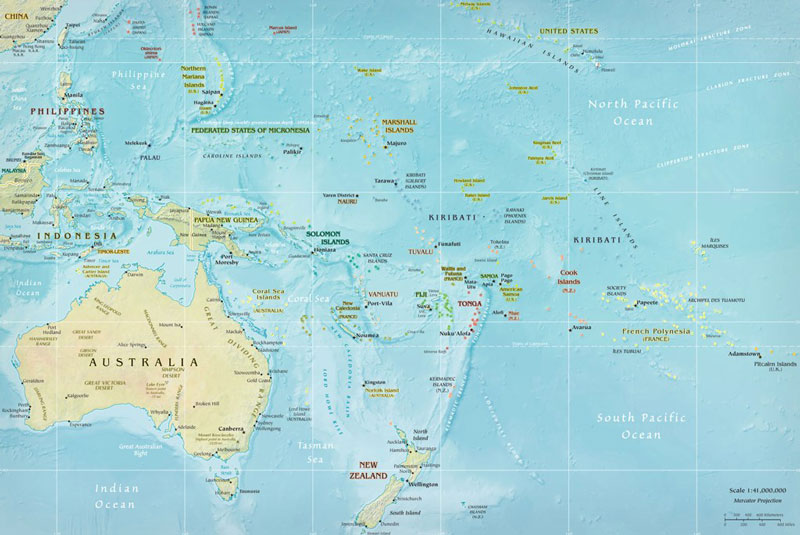

At the same time, Gluckman said, the country must keep close focus on the small island states of the Pacific Ocean. New Zealand's sizeable Polynesian population is a basis for close ties with Tonga, Samoa, the Cook Islands and other South Pacific nations.

At the same time, Gluckman said, the country must keep close focus on the small island states of the Pacific Ocean. New Zealand's sizeable Polynesian population is a basis for close ties with Tonga, Samoa, the Cook Islands and other South Pacific nations.

Those states "have many issues which require a scientific approach – energy security, managing biodiversity and fish stocks, fresh water security and food security", he said, and government-funded New Zealand research organizations are helping to address those issues. But there's a growing focus, he added, on the "complex and urgent issue" of obesity.

Gluckman serves as co-chair of the World Health Organization Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity. And today, the government's Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade is addressing that challenge by both on ground and distance-learning technologies to bring science and health education to these developing countries in the Pacific.

New Zealand also has recognized an important role in climate change: About half of the nation's greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions come from farming sheep, dairy cows and cattle; that makes New Zealand the world's highest per-capita GHG emitter. In 2009, Prime Minister Key proposed that New Zealand could help build a consortium to address issues related to GHGs in food production. The result: today, 47 nations belong to the Global Research Alliance on Agricultural Greenhouse Gases, which is hosted by New Zealand.

Small countries: getting creative

Gluckman cited another carefully targeted science diplomacy engagement: In 2010, discussions with a counterpart in Denmark produced a realization that small countries face particular challenges in the global science community – and big-country models do not offer answers. For example, small countries have more acute choices to make in science prioritisation and they have small domestic markets: factors that change the innovation ecosystem. One result may be that top researchers feel compelled to leave the country for more rewarding work.

Gluckman discussed these issues with the prime minister, and that led to the founding of the Small Advanced Economies Initiative. The six-nation collaboration is focused on science and innovation in small nations.

Last year, Gluckman's office hosted the first global meeting of issues related to providing scientific advice to governments, and he now chairs the planning group for the International Network for Government Science Advice. The Network is planning a capacity building workshop for African nations in March 2016.

These science diplomacy initiatives and others "represent a conscious effort by New Zealand to ensure that we do try to project in practical and constructive ways within the global science community," Gluckman concluded. "It is becoming increasingly obvious that science can be – and must be – an inherent part of our international strategic thinking."

Edward W. Lempinen