Farouk El-Baz can remember, as a child in the 1940s, seeing windmills along the coast in Northern Egypt that generated enough energy to pump water from wells.

They were small, then – short, squat structures with slow-turning, wooden blades – and they were meant only to serve the local community. “We’d go to Alexandria and see all of them, and I’d ask my older brother, ‘What’s these things?’” said El-Baz, who was elected a TWAS Fellow in 1985. “It was a wind energy mill used to pump water for the well.”

In the ensuring years, he would continue to see them whenever he visited the area west of Alexandria. Today, though, they’re all gone. As soon as oil became a major resource in Egypt, the need for local wind energy died out, and wind energy began to seem like a thing of the past.

In the ensuring years, he would continue to see them whenever he visited the area west of Alexandria. Today, though, they’re all gone. As soon as oil became a major resource in Egypt, the need for local wind energy died out, and wind energy began to seem like a thing of the past.

“Rather than the nice quiet mills, now we’ve got these noisy things emitting a lot of smoke into the atmosphere,” El-Baz said. “They thought of that as progress and it really isn’t. It’s reverting to mediocrity.”

Fossil fuels are central to the global identity of the Arab Region in the Middle East and North Africa. The region is a major source of oil, and it is oil that has built much of the region’s wealth and shaped its innovation culture. Yet the region could just as easily be a source of renewable energy, with vast desert landscapes that have rich potential as a home for solar energy plants, and long breezy coastlines that could be lined with wind turbines. Some researchers and policymakers are looking for creative ways to seize this potential – and some believe the effort is long overdue.

Fossil fuels are central to the global identity of the Arab Region in the Middle East and North Africa. The region is a major source of oil, and it is oil that has built much of the region’s wealth and shaped its innovation culture. Yet the region could just as easily be a source of renewable energy, with vast desert landscapes that have rich potential as a home for solar energy plants, and long breezy coastlines that could be lined with wind turbines. Some researchers and policymakers are looking for creative ways to seize this potential – and some believe the effort is long overdue.

El-Baz, a remote sensing researcher who is focused on climate change and environmental science, makes such a case. Interest in improving the environmental sustainability in the Arab region began about 20 years ago, he said. It seemed obvious to many Arab states that they were far behind in green energy, when they should be leaders.

“It’s better to collect energy locally, with plants that they have developed,” said El-Baz. “That idea has caught the attention of countries across North Africa (and the Middle East).”

Read more about the growth of science in the Arab Region in the TWAS Newsletter.

Green energy in the deserts

The Middle East and North Africa, which make up what TWAS calls the Arab Region, is home to over 300 million people. It includes the world’s wealthiest nation per capita, Qatar, as well as some states that in recent years have faced chronic conflicts and unrest, such as Syria, Libya and Iraq. How rich is the potential? If the entire Sahara desert were covered with solar panels, it would produce 1.3 million terrawatts per hour.

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) “region has more potential for solar radiation, more exposure to solar radiation, than any other part of the world,” said Jauad El Kharraz, a Moroccan water management scientist and Head of Research at MEDRC Water Research, who is currently working on a solar-powered desalination project in Oman.”

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) “region has more potential for solar radiation, more exposure to solar radiation, than any other part of the world,” said Jauad El Kharraz, a Moroccan water management scientist and Head of Research at MEDRC Water Research, who is currently working on a solar-powered desalination project in Oman.”

Yet still, some nations are undertaking serious renewable energy projects that could support people there for decades to come.

The global consulting firm Ernst & Young, in its latest Cleantech Survey Report for MENA, ranked Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates (UAE), Morocco and Jordan as having the greatest potential for renewable energy investment in the region. “The opportunities to provide affordable and secure low-carbon energy are continuously expanding,” the report said.

And in a recent blog post, General Electric (GE) executive Hani Majzoub, head of the company’s power conversion sales for renewables across the MENA region, called 2014 “a breakthrough year for solar in the Middle East,” with 30 projects receiving contracts, including 12 new solar sites in Jordan alone.

Perhaps the biggest solar energy boom is taking place in the UAE, which has committed billions of dollars in new clean energy projects over the last four years. The UAE will host what’s expected to be the Middle East’s largest solar project: Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum Solar Park, in the desert 30 miles (48 km) south of Dubai. By 2030 the park should provide 3,000 megawatts – enough to power 50,000 homes and offset over 200,000 tonnes of emissions each year. A large majority of UAE’s power will come from natural gas. But solar will be second, at roughly 15%, followed by coal and nuclear. The plan is to eventually remove oil as an energy source entirely.

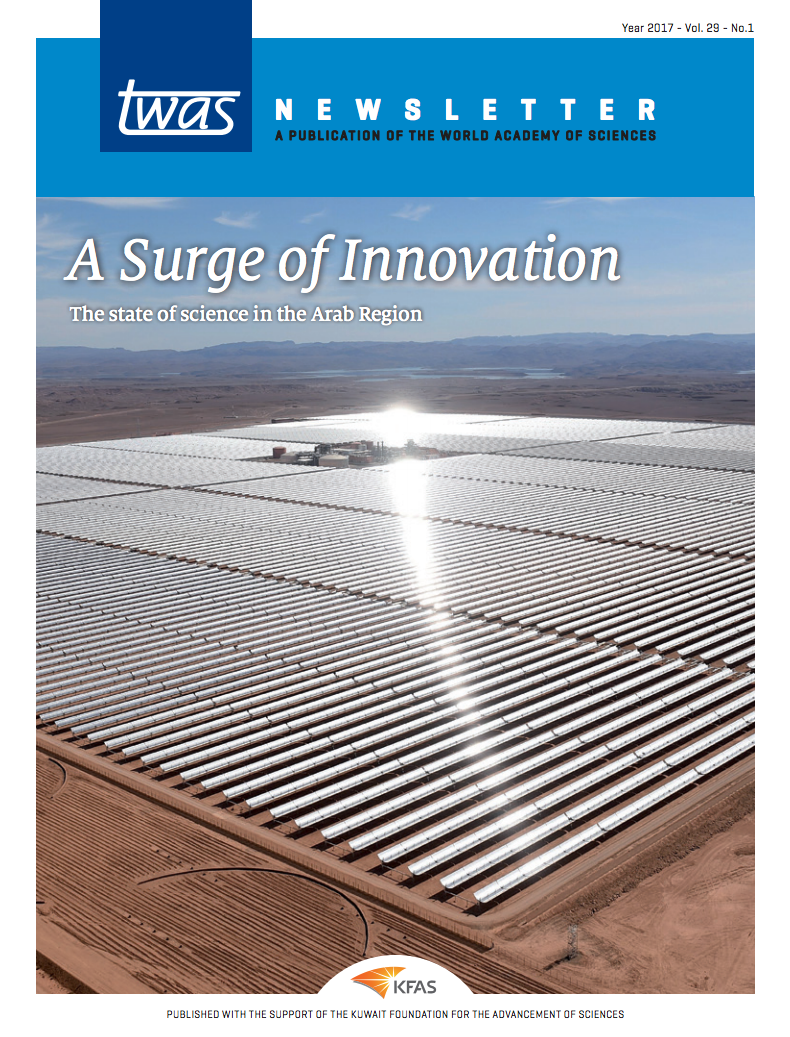

At the other end of the region, 6,000 kilometres west in the deserts of Morocco, the Ouarzazate solar complex is being developed to provide 2,000 megawatts, and is already partially connected to Morocco’s power grid. It is being built in response to climate change and Morocco’s expensive fossil fuel imports. Morocco is not an oil-rich nation – according to the World Bank, it imports more than 91% of its energy resources from other countries. But energy demand is rising quickly, driven by economic growth and a population boom.

Morocco has pledged to draw 42% of its power from renewable energy sources by 2020, and its efforts are being supported by loans and credit backing from international agencies such as the World Bank and the African Development Bank.

A pressing need creates new ideas

To accommodate these and other plans, some innovative work has taken place, finding new uses for renewable technology while also using new methods for generating that power.

Demand is growing. Saudi Arabia opened bids this year for its first solar power plant that will pour energy into its grid. Kuwait is planning to put $1.2 billion into a solar-power plant as part of an effort to generate 15% of its energy from renewables by 2030. In 2014, teachers and students at 25 public schools started receiving power from new solar panels that replaced diesel generators. Even Iraq has explored attracting foreign investors for the creation of three small solar energy projects and a wind energy project.

The United Nations Development Programme has been helping to guide many of these countries toward a more sustainable, greener system in accordance with the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

One innovation developed by researchers in the UAE was a new kind of solar collector that can be attached to the sides of walls like wallpaper. Normally, a solar panel would be a rigidly flat surface attached to a metal base that would move to follow the sun over the course of the day. But such panels are heavy and cumbersome, and expensive to transport and install. So scientists developed a pliable solar energy collector, less than an inch thick, that can be rolled up and even placed on the walls of buildings. It cuts down dramatically on the cost and unwieldy qualities of the solar panels.

“It took them USD15 million to develop it, but it is certainly well worth it,” remarked El-Baz. “It’s in practice around the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Egypt is looking at it, trying to see if they can produce it.”

Winds of change

The emphasis regionwide is mostly on solar energy, though there are some wind projects. Wind projects have found success in the UAE, Jordan and Morocco, but they’ve struggled to receive a strong push in Egypt and Saudi Arabia. And in Tunisia, researchers are exploring completely new ways to use wind energy, including a bladeless device inspired by and emulating ancient sailboats that used an aerodynamic bowl-shaped sail to capture more energy than a traditional turbine. Another device developed by Tyer Wind uses flapping wings, inspired by the mechanics of hummingbirds. A Tunisian inventor, Anis Aouini, is behind both ideas; angel investors in Algeria and Pakistan are backing the Tyer Wind project.

Aouini, the inventor, co-founder and chairman of Tyer Wind, said the current shift toward green technology is a good opportunity for Arab countries without oil reserves, like Tunisia, to flex their innovative might. He anticipates that renewable energy will enter the private sector in Tunisia in two to three years.

Aouini, the inventor, co-founder and chairman of Tyer Wind, said the current shift toward green technology is a good opportunity for Arab countries without oil reserves, like Tunisia, to flex their innovative might. He anticipates that renewable energy will enter the private sector in Tunisia in two to three years.

“We have not had a good experience in recent history in innovation in developing countries in general,” Aouini said. “So it’s a good opportunity for us to demonstrate we are able to develop new technology in Tunisia, manufacture it in Tunisia and commission it in Tunisia. It’s also a way to advance a new economic engine based on green technology. I think this is our future.”

Renewable energy is also being applied in the Arab Region to assist other pressing problems, such as water scarcity. It’s an urgent issue for countries such as Jordan, which has roughly 1.4 million refugees displaced from the conflict in Syria, and Palestine, which has suffered its own long conflict.

Renewable energy is also being applied in the Arab Region to assist other pressing problems, such as water scarcity. It’s an urgent issue for countries such as Jordan, which has roughly 1.4 million refugees displaced from the conflict in Syria, and Palestine, which has suffered its own long conflict.

Desalination is the process of turning undrinkable salty seawater into drinkable fresh water.

El Kharraz, one of four international experts featured in a TWAS roundtable on science and science diplomacy held in Trieste, Italy, said desalination will likely be necessary to provide enough water to people in this part of the world.

But the process consumes a lot of energy. Oil-rich countries can afford it. Those short on oil must turn to another possibility: solar power. “We should find a balance between demand and supply. Most countries are trying to control demand, but we want in parallel to focus also on the supply,” said El Kharraz. “We have a huge amount of water in the sea and desalination allows us to get fresh water from it."

MEDRC is an international nonprofit organization in Oman created 20 years ago. Since its creation, MEDRC has funded over 125 projects. Most deal with desalination technology, the cost of the energy for it, and how to minimize any negative effect on the environment.

El-Baz wants researchers, policymakers and the public all to push for more ambitious energy plans like these. Taking advantage of the region’s massive desert space could open up opportunities to sell power to other parts of the world.

“So,” El-Baz said, “maybe they can sell the ideas or the energy to places that don’t even have a speck of oil.”

Sean Treacy