Some of the most successful pharmaceuticals have come from the plants that surround us in nature – the most famous of which being aspirin, which was first discovered in the bark of willow trees. But there are hundreds of thousands of plant species, so it’s up to scientists to look into them and figure out how their extracts might be useful to medicine.

Some of the most successful pharmaceuticals have come from the plants that surround us in nature – the most famous of which being aspirin, which was first discovered in the bark of willow trees. But there are hundreds of thousands of plant species, so it’s up to scientists to look into them and figure out how their extracts might be useful to medicine.

One place to start is with plants that are already used in traditional healing practices passed down generation to generation since before recorded memory.

Shahdat Hossain, a neuroscientist with Jahangirnagar University in Bangladesh, is looking into one such practice: Use of a plant called the jamun tree. Native to South Asia, the jamun grows large, berry-like fruits. Traditional healers sometimes crush its seeds into a fine powder and give it to people suffering from digestive and respiratory problems. Hossain is taking the jamun seeds a few steps further. He is testing the seed extracts in rats to see if they might help alleviate memory loss in Alzheimer’s disease patients, and used a TWAS grant to get the equipment he needed to do it.

“Since ancient times, the people of Bangladesh have used hundreds of herbs and plants as traditional medicine,” said Hossain. “The scientific grounds of the uses of these herbs and plants has remained largely unknown until recently. In my personal opinion, Bangladesh is simply a fertile place for doing such research.”

The TWAS Research Grants Programme in Basic Sciences for Individual Scientists provides specialized equipment, consumable material and scientific literature to young scientists in 81 countries where financial resources are scarce. It’s supported by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) and provides up to USD15,000 to individual scientists in developing countries. TWAS awarded 44 individual grants in 2013. The deadline to apply for the next grant is 31 August this year.

The TWAS Research Grants Programme in Basic Sciences for Individual Scientists provides specialized equipment, consumable material and scientific literature to young scientists in 81 countries where financial resources are scarce. It’s supported by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) and provides up to USD15,000 to individual scientists in developing countries. TWAS awarded 44 individual grants in 2013. The deadline to apply for the next grant is 31 August this year.

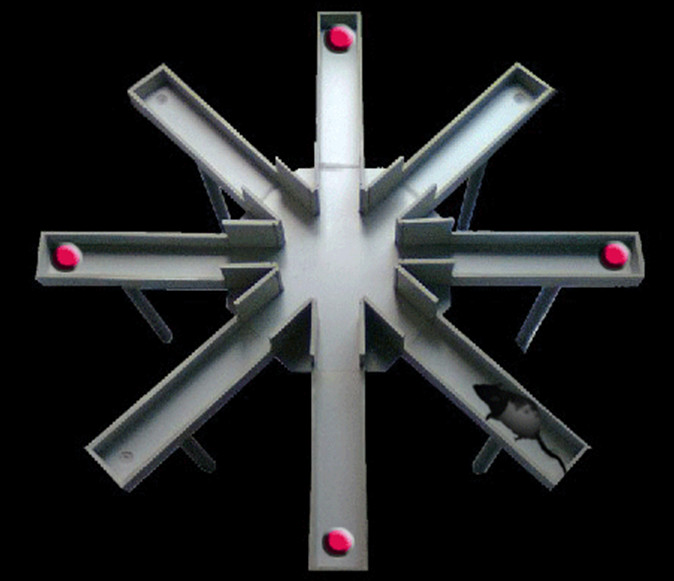

Hossain's team force-fed the extract to about half their rats once a day, and compared them to rats who hadn’t been fed the extract. They routinely placed rats from both groups in a maze with a small circular central room attached to eight linear corridors. Four of these corridors, the same every time, had food at the end. Rats that repeatedly went into the arms they already visited within the same day had a weaker short-term memory. Rats that went into corridors that didn’t contain food the day before had a weaker long-term memory.

Afterward, the team used a special fluorescence microscope to inspect the rats’ brain tissues. They paid USD12,000 for that microscope, their largest expenditure and more than 92% of the total grant. It allowed them to look at the rats’ brain tissues in great detail to determine whether the walls of brain cells were warped or leaking, and also whether the nuclei of those cells were in working order. Most importantly, they were able to color-code different parts of the machinery of those cells, and watch to see if those machine parts were going about their business in the proper way. Their research, Hossain said, showed that the brain cells of rats fed the extract had healthier brains.

Afterward, the team used a special fluorescence microscope to inspect the rats’ brain tissues. They paid USD12,000 for that microscope, their largest expenditure and more than 92% of the total grant. It allowed them to look at the rats’ brain tissues in great detail to determine whether the walls of brain cells were warped or leaking, and also whether the nuclei of those cells were in working order. Most importantly, they were able to color-code different parts of the machinery of those cells, and watch to see if those machine parts were going about their business in the proper way. Their research, Hossain said, showed that the brain cells of rats fed the extract had healthier brains.

“The changes in the expression of a given protein can be detected by this fluorescence microscope,” said Hossain. “These experiments are not possible with a normal microscope.”

Hossain wants to continue his research on extracts from various other plants native to Bangladesh to see if they also slow down the memory loss from Alzheimer’s disease. In the meantime, they are expecting to publish at least two articles in peer-reviewed journals that would have otherwise been impossible without the grant’s help.

“TWAS helped me a lot to enhance our capacity in research, particularly in the visualization of brain slices and its cellular morphology,” he said.

Hossain added that the research also aided the careers of his students. “It enabled my MS and PhD students to do more sophisticated research work in neurochemistry.”

Sean Treacy