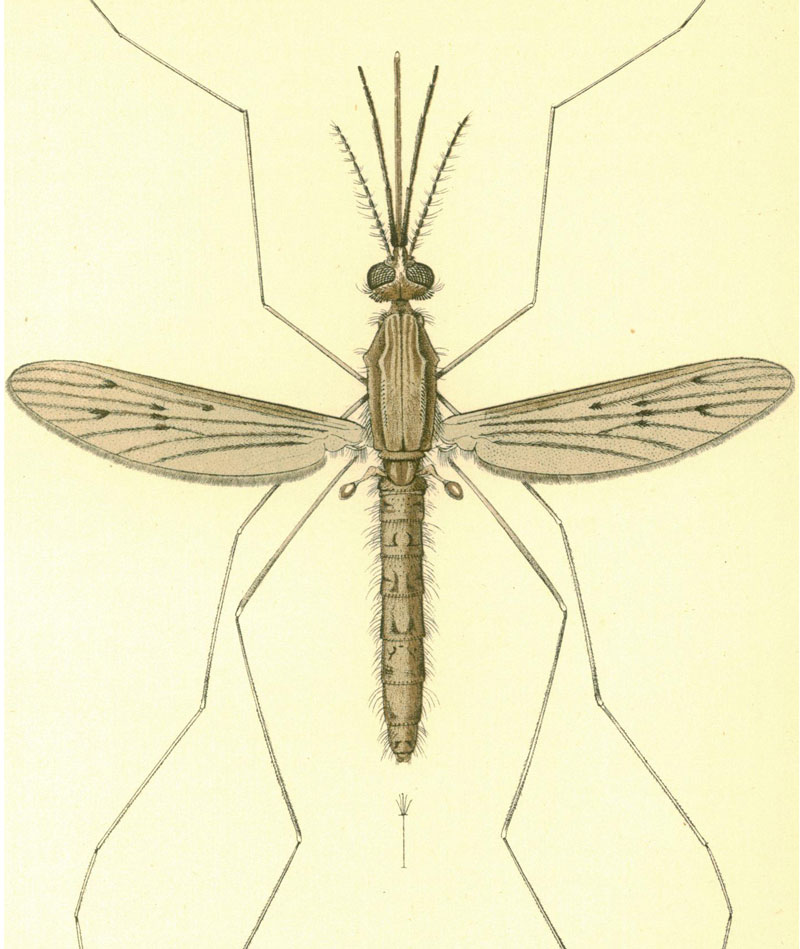

It measures about five millimetres in length, and weighs perhaps five milligrammes, but from a tiny mosquito arises a public health threat of extraordinary complexity: Hundreds of thousands people have been infected by its bite, and tens of thousands have died. And as the government of an impoverished nation works to find a solution, it is struggling through a swamp of tangled issues and conflicting interests.

It measures about five millimetres in length, and weighs perhaps five milligrammes, but from a tiny mosquito arises a public health threat of extraordinary complexity: Hundreds of thousands people have been infected by its bite, and tens of thousands have died. And as the government of an impoverished nation works to find a solution, it is struggling through a swamp of tangled issues and conflicting interests.

Should it seek a solution in vaccines that are promising but very expensive, only partly effective, and opposed by local indigenous healers? Should it authorize the broad experimental release of genetically modified mosquitos, which could block the spread of infection but might ignite opposition from international environmental groups?

The government's dilemma resembles today's battles against malaria, the Zika virus and Ebola. In fact, however, it was a fictional exercise that played out at a recent high-level workshop on the best way to provide science advice to African governments. But for some 40 participants from a dozen nations, the case was a powerful introduction to the difficult decisions that confront both scientists and policymakers who are working to address life-threatening challenges in complex conditions.

"There's never been a more important time for scientists in all fields...to be able to give science advice to their governments," said Roseanne Diab, executive officer of the Academy of Science of South Africa, in remarks that opened the event.

Science has a role is many of society's most important and difficult challenges – health, climate, agriculture and synthetic biology, and extending into issues of gender equality, diplomacy and trade – said Sir Peter Gluckman, chief science adviser to the Prime Minister of New Zealand and chair of the International Network for Government Science Advice (INGSA).

"Science is no longer in an ivory tower," Gluckman said in his opening remarks. "Scientists are no longer high priests standing aside and lecturing society. But that raises a question about how scientists relate to society and to governments....The way science engages with both society and the policy process, and the way these both engage with science, will shape our progress as nations and as a global society."

"Science is no longer in an ivory tower," Gluckman said in his opening remarks. "Scientists are no longer high priests standing aside and lecturing society. But that raises a question about how scientists relate to society and to governments....The way science engages with both society and the policy process, and the way these both engage with science, will shape our progress as nations and as a global society."

Over the course of two days, the workshop organized by ASSAf and INGSA ranged across the broad landscape of science advice to governments. Beyond the conventional issues of science and policy, it touched on the importance of gender balance in this field, the imperative for excellent communication and diplomacy, and the central role of social sciences in shaping effective advice.

ASSAf hosted the workshop on 26-27 February in Hermanus, South Africa. Key support also came from South Africa's Department of Science and Technology (DST); the New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade; and the Wellcome Trust; and The Royal Society in the UK. The workshop was held back-to-back with the General Assembly and Conference of IAP, the global network of science academies.

The event featured speakers and participants from a range of influential science and policy bodies, including Flavia Schlegel, UNESCO assistant director-general for the natural sciences; Richard Mann, the high commissioner of the New Zealand High Commission in Pretoria; and Heide Hackmann, executive director of the International Council for Science (ICSU); plus representatives of the European Union's Joint Research Centre and TWAS.

"A matter of urgency"

The workshop attracted nearly 600 applications – a powerful acknowledgement, organisers said, of Africa's need to build more robust connections between the realms of science and policy. But at present, the quality and influence of science advice to African governments is uneven, reported Thiambi Netshiluvhi, director of policy analysis and advice at South Africa’s National Advisory Council on Innovation (NACI).

In one 2013 study, Netshiluvhi said, less than half of the African ministries surveyed had staff trained in related science, technology and innovation (STI) policy analysis and formulation. But nearly all of those ministries said they lacked sufficient personnel with skills devoted to STI policy analysis and formulation.

"The overall findings suggest that Africa in general has inadequate capacity for STI policy analysis and formulation," Netshiluvhi wrote in a paper prepared for the workshop. "In order for our STI policies to be credible, Africa must work hard to ensure the capacity in policy analysis and formulation is obtained or enhanced as a matter of urgency."

A similar view was offered by Nawal K.N. Alamin, a professor at Sudan University for Science and Technology who specializes in desertification and rehabilitation of dry lands. Alamin is a member of the General Secretariat of Sudan's Popular Congress Party, and she's a committed peace activist. From that perspective, she believes that a robust connection between scientists and policymakers could have a bearing on both her research and her engagement with a community of women peace workers.

A similar view was offered by Nawal K.N. Alamin, a professor at Sudan University for Science and Technology who specializes in desertification and rehabilitation of dry lands. Alamin is a member of the General Secretariat of Sudan's Popular Congress Party, and she's a committed peace activist. From that perspective, she believes that a robust connection between scientists and policymakers could have a bearing on both her research and her engagement with a community of women peace workers.

But, Alamin said: "In my country, and Africa in general, science doesn't play a real role in our political life."

The need is great beyond Africa, too, in both developed and developing countries. Even where science and policy leaders are engaging more often, at higher levels, the relationships are often new, and so they must learn each other's values and language, while respecting the inherent differences that separate the cultures of science and politics.

Gluckman has emerged as a voice of global influence in this field. He was trained as a medical researcher, and then appointed in 2009 as the first chief science advisor to the prime minister of New Zealand. Today, he has a foot in both worlds. In 2014, for example, he served as co-chair of the World Health Organization's Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity. The same year, he helped to organize the first-ever global meeting of science advisers, which brought together 220 delegates from 40 countries in all regions of the world. That meeting led to the formation of INGSA.

During the workshop South Africa, Gluckman and other speakers offered a practical – and often provocative – guide to the conventions and applications of science advice to governments. And, based on their real-world experience, they identified several themes that should guide the orientation of scientists who hope to shape public policy.

1. Science and policy are fundamentally different cultures.

Scientists may tend to think that on issues of science, their insight should be the guiding light for policy. And because the scientific method is designed to neutralize researchers' biases, they may be quick to assume that their policy recommendations are unassailable.

But by looking at the world from a policymaker's perspective, they would recognize that "science is not the only source of knowledge," Gluckman says. "Knowledge comes from many different sources – religion, belief, dogma, family tradition, traditional knowledge."

Inevitably, he said, policymakers must consider knowledge and values that are beyond the realm of science: political ideology, public opinion, balancing the interests of a governing coalition, fiscal limitations.

In Gluckman's view, different cultures and different values lead to a critical distinction: "Policy," he says, "is informed by evidence, but it is not determined by evidence."

2. Cultivate constructive relationships with policymakers, even in countries with weak governance.

A nation's culture and political system will shape how and where scientists seek a connection with government. It might be done through a national science academy, or through a university, or through personal relationships.

A nation's culture and political system will shape how and where scientists seek a connection with government. It might be done through a national science academy, or through a university, or through personal relationships.

But it any context, it is essential for scientists to understand the political process, said Schlegel, who has extensive experience in advising governments and diplomats. "Just bringing your knowledge to the table, that's a good start, but the interaction with policymakers is very important. You have to be timely...

"You also have to be able to talk to all of the stakeholders. Many scientists are very good at talking to other scientists, but you have to be able to talk about your science in a way that it can be understood – by those from the private sector, civil society, NGOs, and governmental representatives. That is not an easy task."

Some workshop participants said their governments had no history of reaching out to researchers, and had shown no interest in such relationships.

Governance, said Gluckman, "is the 64-trillion-dollar question for Africa and for other regions." While organizations such as the United Nations Development Programme and the World Bank have projects to improve governance, people who run governments are sometimes more focused on political survival than on meeting people's needs.

Schlegel said scientists should look into all possible opportunities to speak in support of science policy. "Keep speaking up," she said. "Keep explaining. Keep communicating. Keep alerting. Keep educating. Keep researching. Don't give up."

3. To build the trust of policymakers, minimize arrogance and maximize humility.

Policymakers and scientists have different values and different perceptions of risk. For example, when trying to understand a problem, scientists want extended time for research and study, but policymakers are under pressure to move quickly and efficiently.

On an urgent topic such as teen suicide or an environmental disaster, Gluckman explained, "the worst thing I can say at times to policymakers is: 'More research is needed and more funding is needed for that research to continue'."

Scientists may be confident of their approach to problem-solving, speakers said, but when operating in the sphere of policy, they must accept that policymakers set policy, and the job of scientists and their institutions is to support that process. Violating those terms can mean that science advice will be ignored, and the science enterprise itself may be damaged.

"At the end of the day, trust is the most important thing in this process," Gluckman said. "Trust is easy to break, and difficult to repair."

4. In providing advice, be an "honest broker" rather than an "issue advocate".

There is a time for scientists to lobby for funding and projects, and there may be a place for scientists to offer personal opinions about government policy. But when the government is asking for advice on critical issues, that's not the right time or place.

Speakers at the workshop made a key distinction: If science leaders want to advocate more funding or more research in a given area, they are influencing policy for science. Science advice takes place in the realm of science for policy. But the two generally should not mix.

"The honest broker tries to identify and overcome biases to present what is known, what is not known, what is the scientific consensus, what are the implications for policy and action and the tradeoffs of various options," Gluckman explained. "Scientists often switch between these roles, but when giving advice, clarity as to the role is important. Science advisory systems are best when clearly acting as brokers."

"The honest broker tries to identify and overcome biases to present what is known, what is not known, what is the scientific consensus, what are the implications for policy and action and the tradeoffs of various options," Gluckman explained. "Scientists often switch between these roles, but when giving advice, clarity as to the role is important. Science advisory systems are best when clearly acting as brokers."

"We can do it together"

After two days of expert talks and intensive exercises, many participants felt that it had been a transformative experience.

"This workshop has opened up my eyes," said Anthony Muyepa, director-general of the Malawi National Commission for Science and Technology. "We were dealing with real cases, and this kind of exercise helps me to see where we can step in in Malawi. It's helpful in the way that I plan, and in the way that I try to give advice, and the way I engage other stakeholders."

Karine Ndjoko Ioset, a professor at the University of Lubumbashi and general manager of the Excellence Scholarship Program BEBUC at the University of University of Würzburg in Germany, had a similar view.

Karine Ndjoko Ioset, a professor at the University of Lubumbashi and general manager of the Excellence Scholarship Program BEBUC at the University of University of Würzburg in Germany, had a similar view.

"As a scientist," she said, "I know we have to balance our knowledge with the challenges the politicians are facing. There is always criticism from African scientists about politics, but we are not doing politics, we are doing science. As scientists, we have to be modest...and really also work to build trust.

"We want to change things, and we can do it together."

Edward W. Lempinen