Many scientists have seen the story first-hand: After working for years on a problem such as hunger, energy or climate change, they produce a new technology that can help to answer the challenge. But once that new technology is available, it meets intense opposition from interest groups and the public. They resist the innovation, and reject clear evidence of its value.

Many scientists have seen the story first-hand: After working for years on a problem such as hunger, energy or climate change, they produce a new technology that can help to answer the challenge. But once that new technology is available, it meets intense opposition from interest groups and the public. They resist the innovation, and reject clear evidence of its value.

It's an old pattern. The invention of mechanical refrigeration in the mid-19th century alarmed the ice industry and triggered debates over the safety of refrigerated food. More recently, genetically modified, pest-resistant crops have met resistance from two groups: an agricultural sector with deep ties to the pesticide industry and activists who warn of environmental and health dangers, in spite of robust contrary evidence. And renewable energy technologies, urgently needed to counter climate change, face opposition from the fossil fuel industry and political factions that deny the reality of warming.

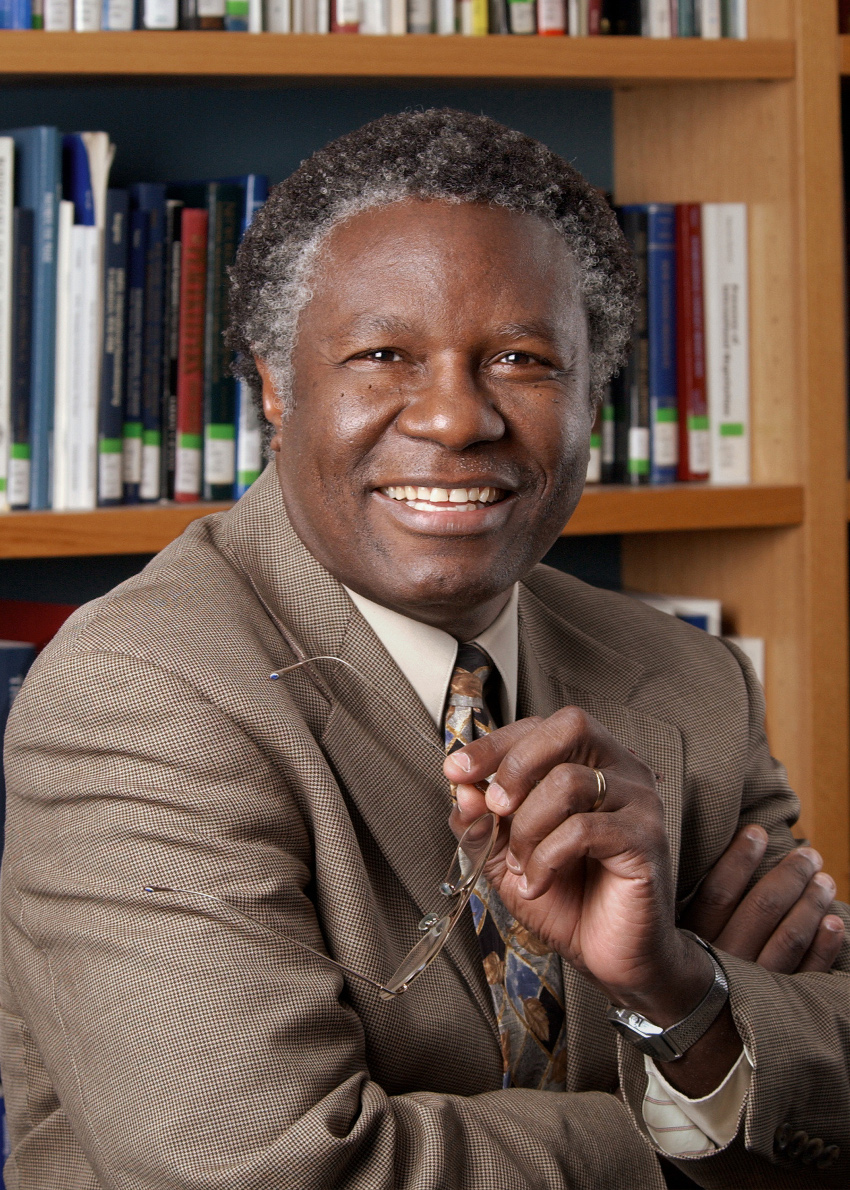

TWAS Fellow Calestous Juma explores this dynamic in a new book, “Innovation and Its Enemies: Why People Resist New Technologies" (Oxford University Press, July 2016). People don’t fear emerging technologies because they are new, Juma says. Rather, the resistance typically comes from established industries and social orders that feel threatened by the new technology's superiority and worry about being displaced. In this way, new technologies generate uncertainty about the future – and when making decisions under uncertainty, potential losses loom larger in people's minds than potential gains. They fear what might be lost – financial and political power, even their cultural identities.

They forget that inaction also carries a risk, Juma said. “So the rate at which we apply new technologies tends to be glacial.”

Juma is professor of the practice of international development at the Harvard Kennedy School in the United States. He was born and raised in Kenya, named a TWAS Fellow in 2005, and is now a leading voice on issues of biotechnology and science and innovation policy. This is his second book, following “The New Harvest: Agricultural Innovation in Africa”.

In an interview, Juma said he wrote ‘Innovation and its Enemies’ because very few new technologies generated today are ever actually put to use. These emerging technologies become stuck in limbo because the public discussion shifts from fixing the problem to debating the technology. And each chapter in the new book serves as a case study of resistance to a new technology.

Coffee, for example, is among the oldest transformative innovations. It was first domesticated in the 15th century in what is now Yemen, outside its origin in Ethiopia. It started to get consumed at mosques to keep imams awake and summon people to prayer. But coffee spread to the general public and coffee houses surpassed mosques as the main social centre where people met and exchanged ideas. So a question rose around social control. Religious leaders began arguing whether coffee was intoxicating in way that was similar to wine, which had been banned from Islam, and they expanded the idea of intoxication to include coffee.

Coffee won out in the end. And it continued to spread to Europe where it faced competition all over again, this time from beer and winemakers.

The pattern repeats itself throughout history. Margarine faced challenges from the dairy lobby. Horse-breeders opposed farm tractors. Musicians secured bans on recorded sound.

More recently, resistance to transgenic crops emerged. Transgenic crops are genetically engineered plants that help control pests by inserting genes that make them to produce their own insecticides. This allows farms to increase food production while reducing use of chemicals.

More recently, resistance to transgenic crops emerged. Transgenic crops are genetically engineered plants that help control pests by inserting genes that make them to produce their own insecticides. This allows farms to increase food production while reducing use of chemicals.

“The dynamics of resistance to new technologies have not changed at all,” Juma says. “The methods used to fight coffee in the Middle East (in the 16th century) are very similar to the methods used to fight GMOs in the modern day."

Ironically, scientists developed transgenic crops at a time of deep worries about how chemical pesticides could harm human health and the environment. Still, transgenic crops ran into opposition from governments, environmental groups and consumer organizations all over the world. And while many of their concerns may have been well-meaning and worthy of close evaluation, they continued despite ever-increasing evidence that the new crops were beneficial to both health and the environment.

Such useful technologies run into a wall again and again. But the point of the book, says Juma, is not to argue that new technologies are never harmful. From asbestos to cigarettes, there are numerous innovations that have had tragic ends. The problem is that the stories of those harmful technologies become the reference points by which all new technologies tend to be judged, even if they’re proven safe.

While policymakers and the public may have legitimate concerns about new technologies, Juma argues that scientists often run into political rhetoric that focuses on the imagined risks unsupported by evidence rather than established risks. This rhetorical model assumes that doing nothing is a risk-free choice.

The debate can spin out of control. Often, public consultations designed by activists are interested in completely different problems than those the technology was developed to solve. Or established industries fight to slow down the pace of technological change to prevent competition. Suddenly, the dialogue is no longer about using research to solve pressing problems.

“And then at that point it becomes a political process," says Juma. "It’s not about science. It’s about politics.”

'Innovation and Its Enemies’ functions partly as a warning about these hazards, and Juma hopes the book will serve as a guide for scientists and their supporters on how to strategically deal with opposition to their ideas.

The key advice he offers is that uncertainty could be a benefit or it could be a loss, depending on your standpoint. Those benefitting from the status quo will see the potential loss. Others might yet see the potential for benefit.

Researchers should make sure that people or groups who could benefit are involved in the debate. For example, when there’s a discussion about GMOs, bring in the farmers who would benefit from the technology. Otherwise governments will only hear fearful voices and will be too nervous to implement the technology.

"Much of the debate on the role of technology is based on hypothetical claims, with no real products in the hands of producers or consumers," he argues in the book. "Under such circumstances, communication and dialogue are not enough until there is a practical reference point. In other words, rebutting the claim of critics is not as important as presenting the benefits of real products in the marketplace."

It's important to bring in existing industries and other groups who will also feel the effects of the change and could perceive potential losses. A sense of exclusion, he says, is what drives much nervousness about potential losses, and thus opposition to new technologies.

Innovation and its advocates have to bring with them a spirit of inclusion, to emphasize how the technologies can improve people's lives and help address unmet needs. "In an increasingly complex and uncertain world," Juma writes, "the risks of doing nothing may outweigh the risks of innovating."

Follow Calestous Juma on Twitter (@calestous) for further updates and discussion on the book.

Sean Treacy