KIGALI, Rwanda – High-level representatives of five African nations have ratified an ambitious call to improve university-level science and engineering education through new policies, investments and global partnerships.

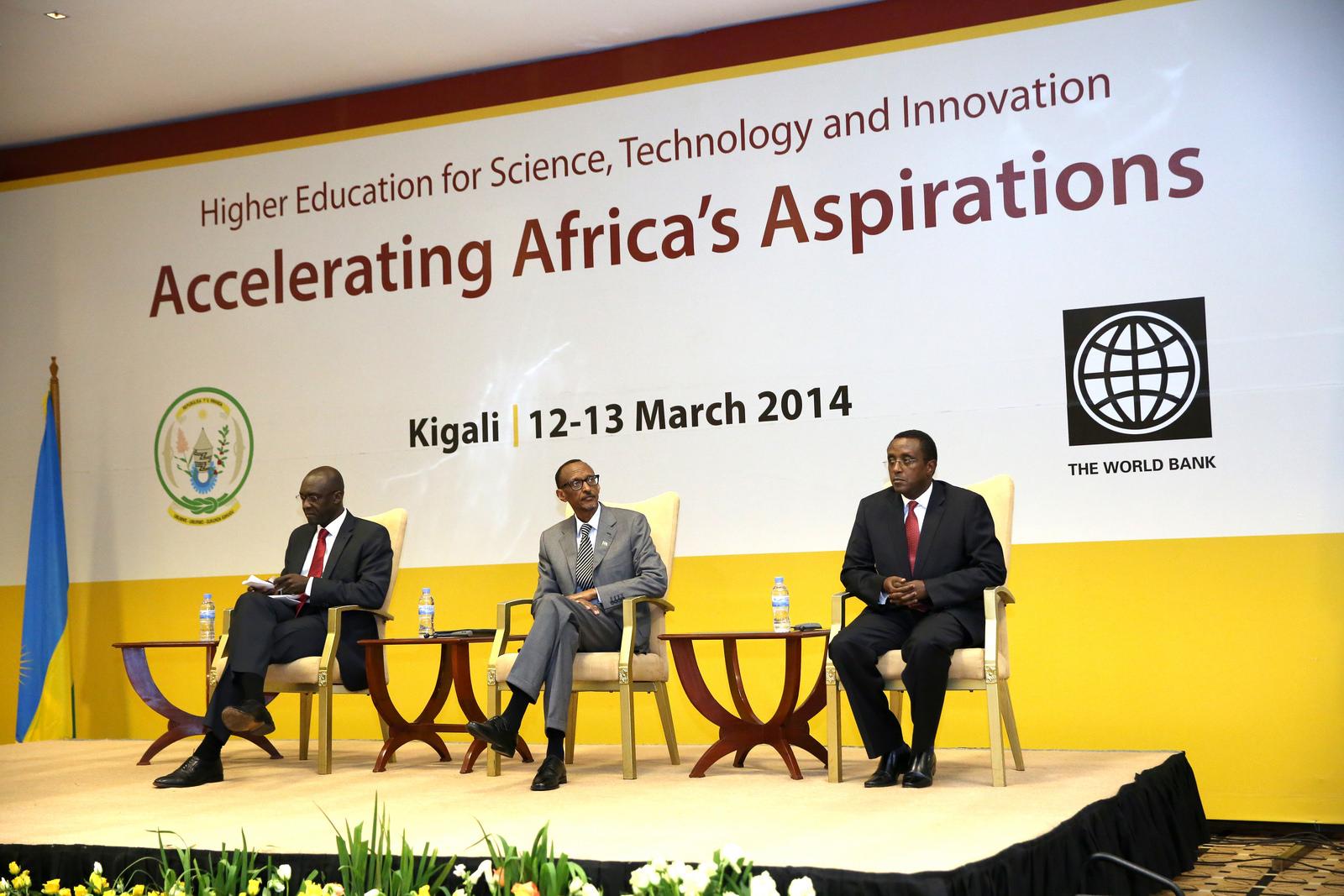

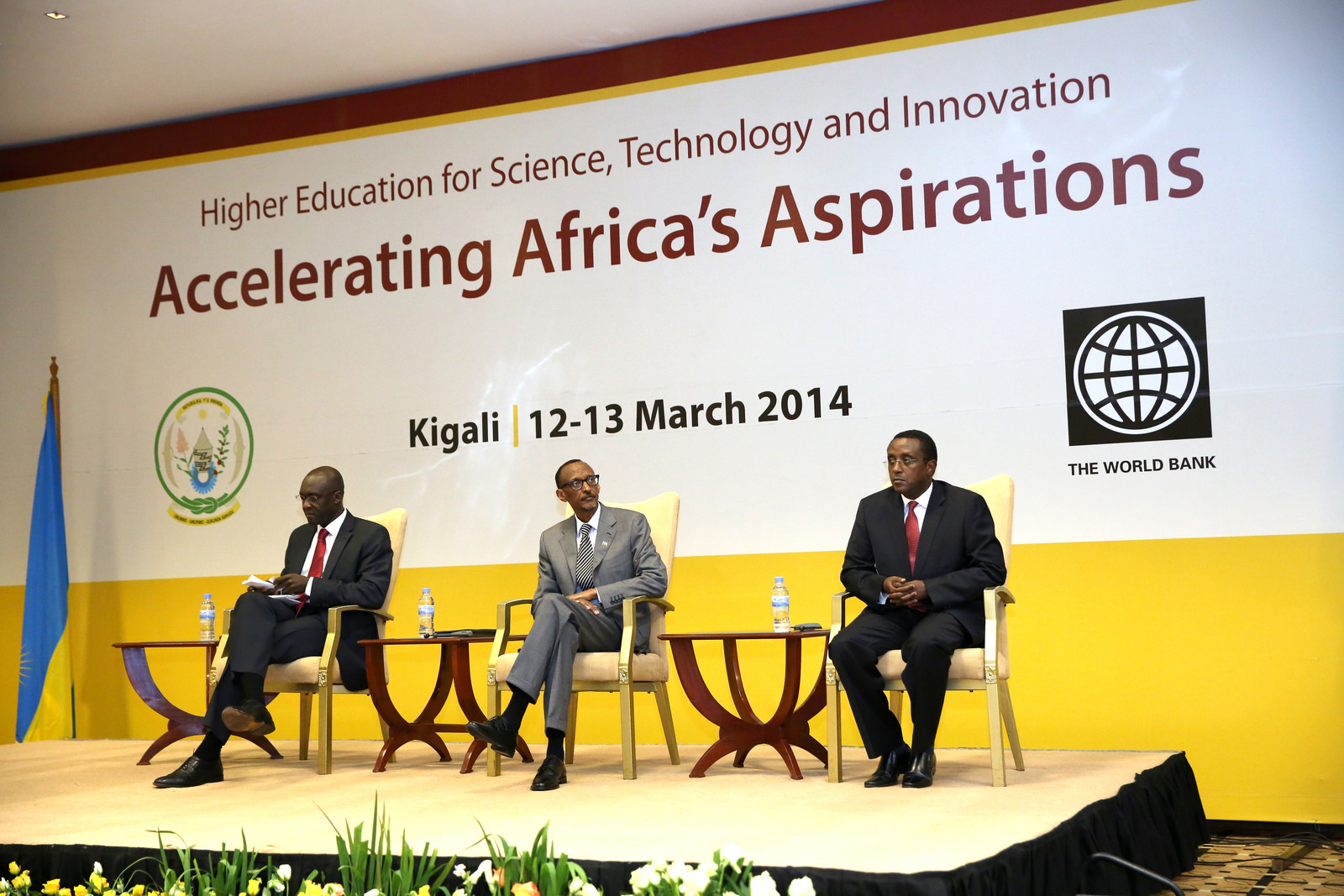

The call to action was approved at the end of a two-day forum organized by Rwandan President Paul Kagame and the World Bank. Science and education ministers from Ethiopia, Mozambique, Rwanda, Senegal and Uganda pledged an "ambitious commitment" that would comprise a  systematic effort to produce more African scientists and engineers to support sustainable development and human prosperity across a continent of 1 billion people.

systematic effort to produce more African scientists and engineers to support sustainable development and human prosperity across a continent of 1 billion people.

The forum was attended by Kagame and leaders from the African Union, the African Development Bank, TWAS, IAP – the global network of science academies, UNESCO and other influential advocates of Africa's emerging knowledge economy.

"I welcome the commitment to strengthen and mobilise resources for building capacity in science and technology, in our pursuit of Africa’s socio-economic transformation," Kagame said in the forum's closing address on 13 March. "Our collective commitment must be followed by concrete action to drive innovation for the development of our people and our continent."

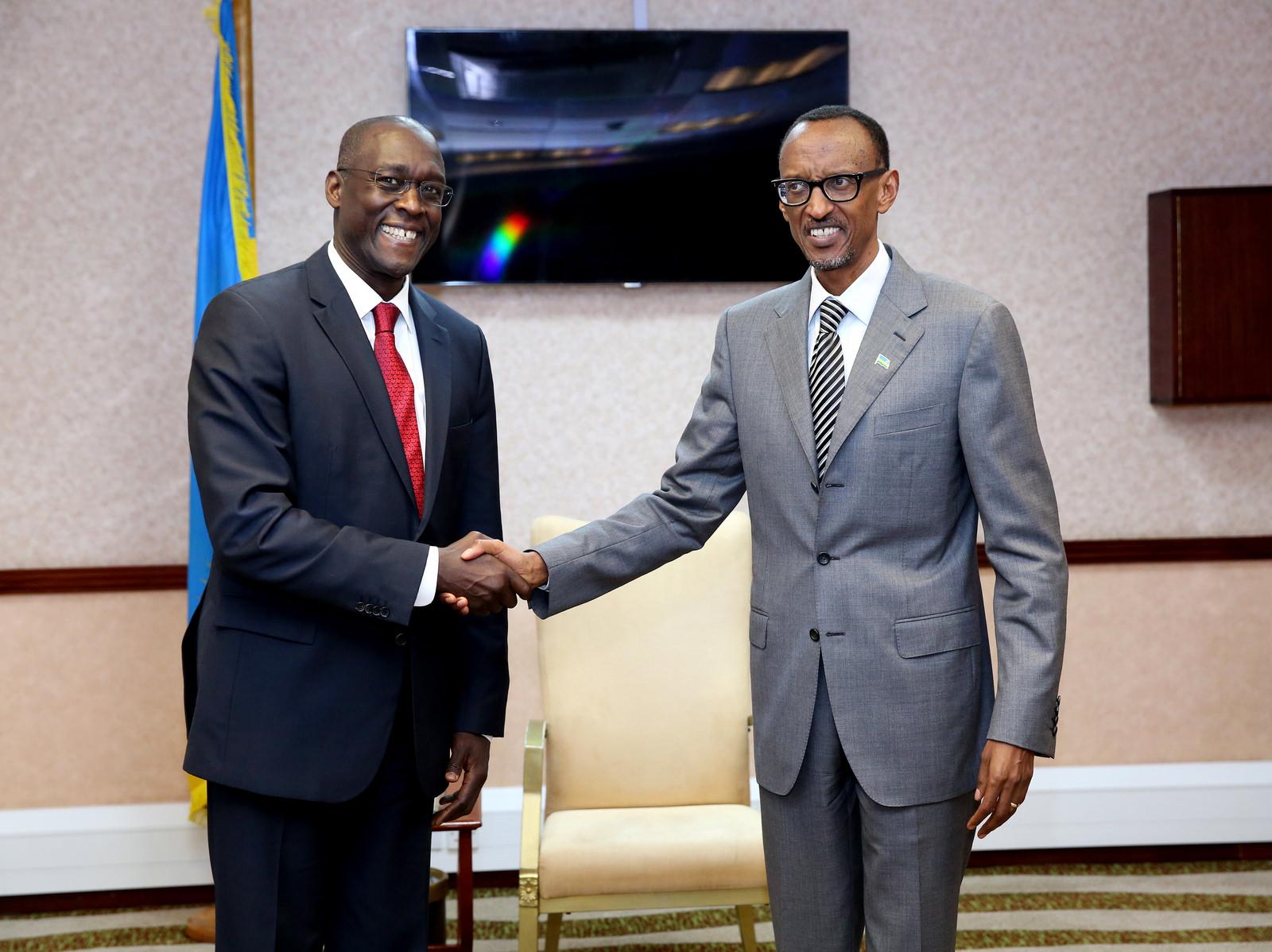

Makhtar Diop, the World Bank’s Vice President for Africa, also urged the forum participants to set transformative goals.

"To be more competitive, expand trade, and remove barriers to entering new markets, Africa must expand knowledge and expertise in science and technology," Diop said in the keynote address. "Let us set some bold targets: that we will see a doubling of the share of university students graduating from African universities with degrees in mathematics, science and technology by 2025. The time has never been more auspicious to focus on higher education, particularly in science, technology and mathematics.”

The five-page communiqué [see link at bottom of page] ratified by the governmental representatives prescribed a broad range of efforts to "transform the primary resource-based economy into an innovation and knowledge-based economy". Higher education and a growing corps of PhD scientists and engineers are seen as a key to that transformation. To achieve the goals, the communiqué called for policies and resources to increase enrollment – of women, especially – in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields. And it called for greater investment in information and communications technology and closer partnerships with business leaders and the African diaspora to build the strength of universities and technical schools.

The "High-Level Forum on Higher Education for Science, Technology and Innovation: Accelerating Africa’s Aspirations” was held 12 and 13 March in Kigali, the Rwandan capital. It convened some 250 participants, including leading policymakers, educators, and representatives of the private sector, funding agencies and science organizations.

Among the key participants who shaped the final communiqué were high-level government ministers of science and education from five nations: Vincent Biruta, minister of education, Republic of Rwanda; Mary Teuw Niane, minister of higher education and research, Republic of Senegal; Jessica Alupo, minister of education and sports, Republic of Uganda; Ato Wondwossen Kiflu, state minister for technical and vocational education and training in the Ministry of Education, Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia; and Arlindo Chilundo, deputy minister of education, Mozambique.

TWAS had a significant role at the meeting. Mohamed H.A. Hassan, co-chair of IAP, the global network of science academies, and chairman of the Council of United Nations University, delivered the keynote address at the inaugural ceremony; Hassan is TWAS’s treasurer and former executive director. On the forum’s second day, Executive Director Romain Murenzi gave an address and chaired a panel that focused on S&T lessons from other nations. Fernando Quevedo, director of the Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) in Trieste, Italy, and a TWAS Fellow, spoke in a panel on the relationship between science and business in Africa's development. Lidia Brito, director of UNESCO’s Division of Science Policy and Capacity Building, chaired a session that shaped the forum’s final call-to-action statement; she has represented UNESCO on the TWAS Steering Committee. TWAS Public Information Officer Edward W. Lempinen served as the master of ceremonies on both days.

In addition, the forum featured high-ranking representatives from the African Development Bank and the governments of China and India, plus other participants from Belgium, Japan, South Korea, Sweden, the United Kingdom, the United States and the European Union. Representatives from Intel, Microsoft, Elsevier and other global businesses also attended.

"Profound Implications for Young People"

Through the forum's two days, all of the presentations and discussions focused on a common theme: How can Africa's disparate nations cooperate to build the strength in higher education that is needed to support the continent's science and engineering sectors?

Africa, for at least the next decade, is facing a set of interlocking challenges.

Its population, currently about 1.1 billion, is growing more quickly than any part of the world. Today, some 40% of the population in sub-Saharan Africa is under 15. This "demographic dividend" can be a huge source of energy, creativity and economic growth, but only if there are education and jobs for the estimated 11 million young people who will enter the job market every year over the next decade.

At the same time, African leaders look to nations such as China, India and Brazil and they recognize that science and engineering are essential for economic growth. Scientists and engineers are needed in virtually every sector of the economy, from agriculture and health services to infrastructure engineering and adapting to climate change.

In all, speakers said at the Kigali forum, Africa will need hundreds of thousands of new scientists and engineers in the coming decades. But the educational system, in its current condition, does not have the capacity to teach and train them.

"What we are gathered here to do has profound implications for young people in Africa,” Tawhid Nawaz, the World Bank's director for Human Development in Africa, told the audience on the forum's first day. “Essentially, young people can take advantage of economic opportunities only if they have the right knowledge and skills.”

"Training PhDs is not a luxury"

Hassan, in his keynote address on the first day of the forum, offered a big-picture view of Africa's challenges – and potential solutions.

Science and technology will be critical for sustainability and economic transformation in Africa, Hassan said. But building a strong S&T sector"will require improving the quality of scientific research and training in higher education institutions to develop a new generation of talented problem-solving researchers."

Centres of excellence in science and engineering are "critically important" for every country, he added. Not only do they attract top researchers, but they also attract political and funding support and become hubs of international cooperation. And merit-based science academies are an essential resource that can "mobilize accomplished scientists, mentor young talent and advise government" on science and science education, Hassan said.

Other speakers, including Kagame and World Bank experts, also emphasized the value and potential impact of centres of excellence. Diop said the World Bank's Board of Directors will soon consider an Africa Centers of Excellence Project, which will bring together universities to focus on common development challenges in extractive industries, energy, environment, health, agriculture, internet communication and technology and other areas.

Murenzi, the TWAS executive director, urged African leaders to recognize the central importance of educating and training PhD scientists.

"Every new PhD scientist and engineer is a source of strength for their nation," he told the audience.

But Africa's PhD deficit is profound. In the United States, there are 1,580 PhD scientists per million residents. In South Korea, there are nearly 1,200. But many have African nations have fewer than 100 scientists per million residents – and some have fewer than 20.

Inevitably, Murenzi said, a PhD deficit results in a science deficit. Africa has 14% of the world's population, but it accounts for only 0.8% of annual global investment in research and development and produces only 2.3% of the world's annual published research.

"If we say Africa should be training one PhD for every 1,000 students, are we today training 10,000 PhDs?" Murenzi asked. "If we say we should be training one PhD for every 250 students, are we training 40,000 PhDs? That is probably the number that should be our target.

"It is a real challenge. But training PhDs is not a luxury...They are researchers, they are teachers, they are mentors. They provide science advice to governments, and they help bring their countries into international research networks."

A race to build universities

Government representatives at the forum made clear that a university-building boom is underway in their nations, essential to support soaring enrollments.

Ethiopia had just two universities in 1996; today, it has 31. Kenya has 15 new universities focused on science and technology. Uganda is adding a seventh public university and is building new ties between higher education and the business sector.

Rwanda had some 3,000 students enrolled in university in 1995-1996, and now has 84,000. To address the challenge of improving quality in Higher Education the Government of Rwanda has recently merged all of its public universities into a new University of Rwanda. At the government's invitation, prestigious United States-based Carnegie-Mellon University has opened a campus in Kigali.

And the International Centre for Theoretical Physics will open a branch in Rwanda, making new PhD, master’s degree and fellowship programmes accessible in the country.

The University of Rwanda's academic staff reached 3,500 in 2013, a 46% jump in just two years. That represents remarkable growth, but it also presents a challenge: Fewer than 20% of academic staff have PhDs, said James A. McWha, the university's vice chancellor. To support the progress to a knowledge-based economy, the number should be closer to 80%, he said.

Others, too, said that policymakers are working against a difficult challenge: making sure that facilities, faculty levels and overall educational quality advance as quickly as enrollments – or faster.

The forum's final communiqué offered a detailed map that could lead to that goal.

High-level government leaders from Ethiopia, Mozambique, Rwanda, Senegal and Uganda agreed to work together to support S&T initiatives "that aim at strengthening higher education and other knowledge institutions." Among the specific goals: strengthen science and mathematics education at all levels; reform tertiary education to build science and technology capacity; increase the enrollment and employment of women in science, engineering and technology; invest in research and development; establish closer ties with the private sector; and engage with the public to build broad support for science, technology and innovation.

"The challenges of African higher education are enormous," Diop said. "Today, the tree of knowledge can grow only if we take care of the roots and the leaves."

Edward W. Lempinen

For more information:

- The closing address of Rwandan President Paul Kagame

- The keynote address by Makhtar Diop, the World Bank’s vice president for Africa

- The World Bank's video of the Forum's second day (in 9 sections)

- Prof. Romain Murenzi's slide presentation

- Prof. Mohamed Hassan's slide presentation